Climate crisis is the leading concern for humanity among young scientists and Nobel laureates at Lindau Meeting

Survey at the 72nd Lindau Nobel Laureate Meeting

By Daniel Koch, Postdoc at the MPI for Neurobiology of Behaviour - caesar, Bonn

Every year, several dozen Nobel laureates and a few hundred of the most promising young scientists in their field gather together on the small island Lindau on Lake Constance in Bavaria. A charming place full of small alleyways that invite for a stroll, beautiful architecture, and a stunning view of the Alps in the background. The unique atmosphere of this place begets stimulating discussions in which the best scientists from all the over world search for solutions and exchange ideas on how to address the big issues and questions in science and society - captured by the motto “educate, inspire, connect”. Needless to say, I was honoured and overwhelmed by excitement when I received the invitation to attend this extraordinary meeting.

What are the biggest issues of our time though? Not that there’s a lack of problems. On the contrary - the outbreak of the Ukraine war and other smouldering conflicts, the risk of further pandemics, the spread of antibiotic resistance, and a climate crisis that starts to spiral out of control can make it hard to prioritize where to focus our limited attention.

Sitting on the train to Lindau, I began wondering what the people at the Lindau meeting, most of whom are way smarter than me, would think about this question. Despite being a little afraid to make a fool out of myself, I decided to find out. “What do you think is the biggest challenge or threat to humanity within the next 100 years?” I thus asked almost everyone I happened to have a conversation with. It turned out many were quite glad for the opportunity to talk about their biggest concerns. Here’s what they said.

Among the 101 young scientists whom I asked, the climate crisis (by a large margin) was the leading cause of concern for humanity, followed by various concerns about AI and its implementation and war and conflict. In some of the more extended discussions about the climate crises, a significant number of my colleagues (myself included), began wondering whether their efforts to e.g. find novel therapies will actually still make a difference. Translating scientific insights into novel therapies often takes decades, a timescale during which we can expect the climate crises to already take a significant toll on our health. Without ramping up meaningful climate action, our health expectations worldwide may actually be worse despite ongoing scientific and medical progress.

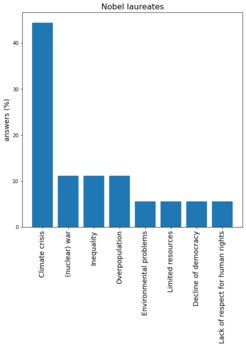

The dozen Nobel laureates I talked to painted a similar picture. Although they were generally less concerned about the dangers of AI, the climate crisis made it to the top of their list, too, and most of the laureates I talked to were supportive of urgent and ambitious climate action.

While this year’s Lindau meeting was dedicated to medicine and physiology, the various ways in which the climate crisis is detrimental to our health and how we as scientists might contribute towards a sustainable future were also brought up at the panel discussion on Climate Change and Implications on Health (www.mediatheque.lindau-nobel.org/recordings/41080). The perhaps most important point raised in this discussion, however, is that we do not need more discussions, but implementation. A point that also was similarly brought up by Nobel laureate Jacques Dubochet (www.mediatheque.lindau-nobel.org/recordings/41068) who joined the GrandparentsForFuture to highlight the urgent need to address global heating.

Implementation of climate action, however, is still prevented and delayed mostly by politicians who either do not understand (or do not want to understand) the seriousness of the situation or put vested interests above the interest of their children, their country and the whole planet. Scientists have been publicly warning about the dangers of climate change for decades, the effects of which we are beginning to see. While their warnings often were and still are met with stunning and often deliberate ignorance, we as scientists, too, are not powerless and can contribute to transitioning towards a more sustainable future – even if our research has nothing to do with climate or energy. How? Here are some suggestions:

- Organize! This is perhaps the single biggest thing you can do, because only if enough people come together can meaningful change be brought about. Join some party, a climate group of your liking or, if you’re part of the Max Planck Society, join our sustainability network and the local sustainability group at your institute (...duh!). Similar interest groups may exist at your university. If there isn’t one, look for some likeminded folks and set one up!

- If you have a lab and work in the biosciences, there are often plenty of ways to reduce waste and energy consumption (e.g. changing ULT-Freezers from -80 to -70oC). Check out e.g. www.mygreenlab.org for more information.

- Find out what your pension funds are invested in and if possible, lobby for divestment from fossil fuels at your institution (see for example www.sustainvbl.de)

- Ask if solar panels can be set up at your university/institute where possible.

- Ask publishers like Elsevier not to provide services to the fossil fuel industry anymore.

Pick one and when you’re done, pick another one and repeat! ;-)